Against the Naturalization of What Can Be Changed

My project addresses the environmental crisis by arguing that fostering real change requires a radical shift in the assumptions underlying our ways of life. My thesis advocates for a transformation of our societal structures, opposing superficial adjustments, such as current sustainability policies, thus creating the space for new narratives to flourish. Developing these new narratives requires a multidisciplinary approach, given the complexity of the issue and the different spheres in which our assumptions operate.

The ways in which we think about the environmental crisis must be transformed, beginning with a modification in the assumptions underlying our habits.

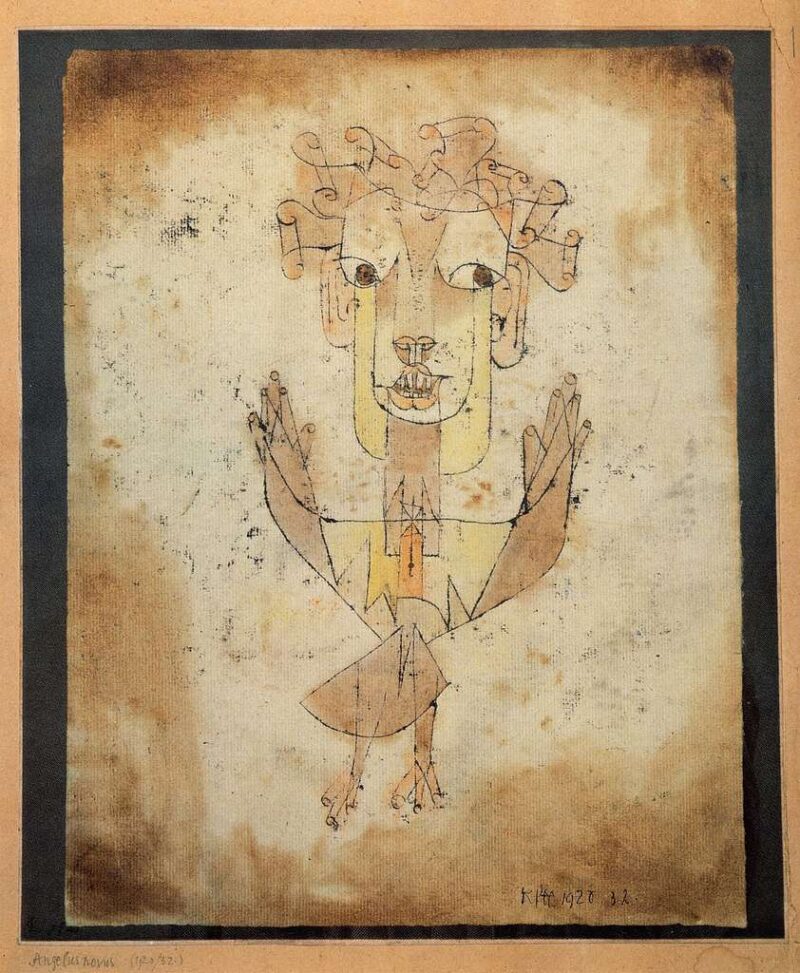

The system we live in is modifiable, struggling against the false notion that there is no alternative. In our societies, it is common to present most of our rules, organizational praxis, and general assumptions as the result of nature. The naturalisation of something that is, in reality, the product of a process entails the belief that this something is eternal, static, and necessary. Consequently, it is always assumed as true and immutable, so that even when it is the source of the problems we are trying to solve, it remains untouched and continues to cause the same issues.

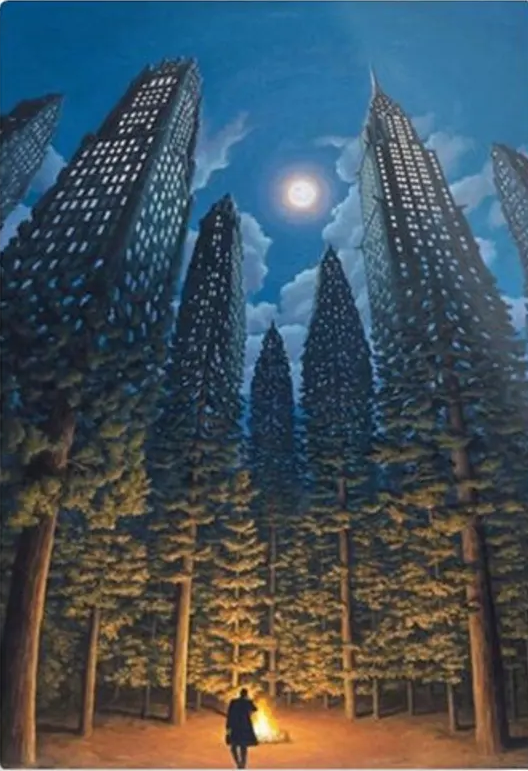

One of the most significant assumptions impacting the environment is the belief in the world as an immanent utopia. In Western societies, the world is mainly understood as ready to be shaped by the projects humanity wants to fulfil, and seen as an infinite world at our disposal. Normally, utopia should represent something that is not yet realised; in contemporary society, utopia is instead an immanent vision, lacking projection, and it moves not within the order of possibility as much as of the already realised.

The public discourse, around climate crisis too, is then shaped so that it does not invite a proactive attitude, but rather the acceptance of the status quo or, at best, short-term actions designed mainly to achieve maximum well-being with minimal effort and change. Emblematic of this attitude are the assumptions underlying the most recent sustainability policies in the organization of work.

There is no necessity in the way we live, work, and think. This entails the understanding of the world as a utopia in fieri. A true utopia arises from the necessity of modifying reality. My project aims to apply this kind of utopian thought to the discourse around the environmental crisis. We should envision the world as the product of many processes and practices that we have put in place. Understanding the world as a realised utopia prevents us from radically change our ways of life, whereas the idea of a utopia that has yet to come and has to be build encourages a proactive attitude and real engagement in exploring different solutions.