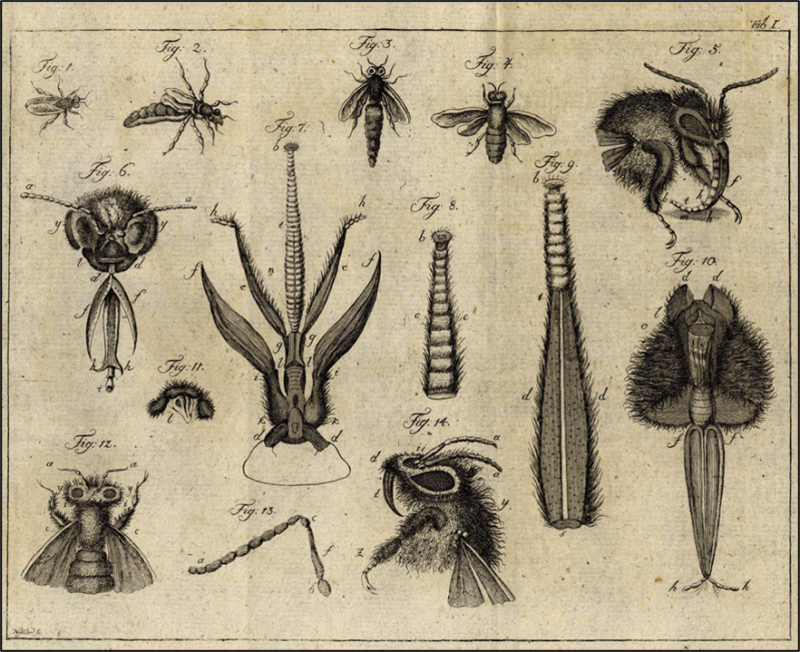

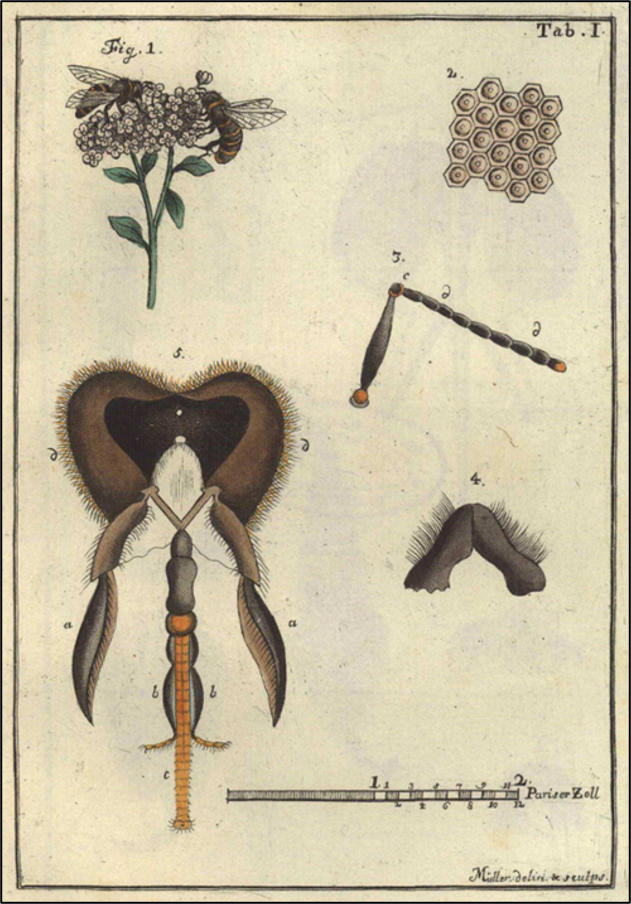

Schirach, Adam Gottlob, Melitto-Theologia, Dresden 1767

Honeybees and Humans: A More-than-Human History of Knowledge around 1800

Humans and Honeybees is a project in the history of knowledge, situated between historical anthropology and animal history. Drawing on texts, images, and material culture from around 1800, it explores how human encounters with honeybees shaped both ecosystems and societies. By tracing their entangled histories, the project examines the more-than-human dimensions of (early) modern knowledge production, focusing on a small insect and its complex relations with the human world.

Christ, Johann Ludwig, Naturgeschichte, Klassification und Nomenclatur der Insekten vom Bienen, Wespen und Ameisengeschlecht, Frankfurt am Main 1791

In the Age of Enlightenment bee-related scientific publications saw a remarkable boom: Pastors, natural historians, poets, and illustrators alike discovered their fascination with honeybees, bringing these inconspicuous creatures—and their honey, buzzing, and proverbial orderliness—into the focus of naturalist attention. Around 1800, enthusiasts from diverse backgrounds admired, bred, and studied honeybees, presenting their discoveries through various kinds of texts, illustrations, and artifacts.

Focusing on the late 18th and early 19th centuries, my project examines honeybees as objects of scientific curiosity and emotional engagement. Combining insights from animal history and historical anthropology, I investigate how different techniques of natural history, modes of entomological observation, and the resulting emotional and sensory experiences affected both humans and honeybees.

Using a wide range of sources—including treatises on beekeeping, scientific illustrations, etchings, and historical insect collections—I trace the complex entanglements between humans and honeybees. These textual, visual, and material sources show how this long-standing relationship unfolded, highlighting the entangled histories of humans, insects, and the environments they have shaped together.

In this way, I argue that the history of (early) modern entomology should be understood not only as a series of zoological classifications, taxonomies and descriptions, but also as a history of sensations, emotions, and knowledge inspired by animals. Through this, I aim to contribute to discussions about the more-than-human, affective, and sensory dimensions of knowledge production.