Post by PhD Students Floris Winckel and Livia Cahn

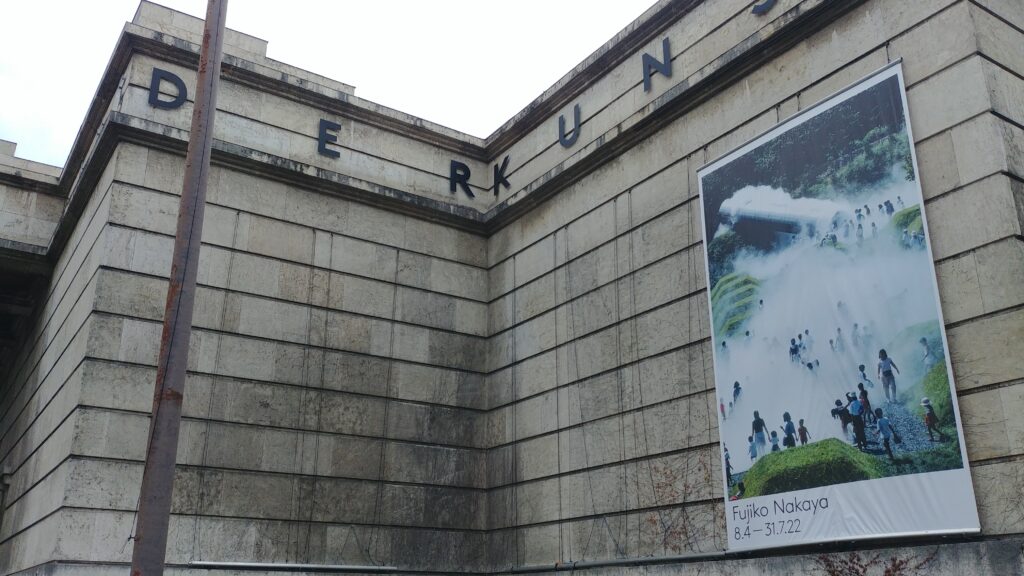

On Thursday April 7th, 2022, the Haus der Kunst in Munich opened a pretty special exhibition. Titled “Nebel Leben” (“Fog Life”), it surveys the work of Fujiko Nakaya (b. 1933), a Japanese artist whose career stretches over seven decades. Her work has been on display around the world, and ranges across multiple different media. But she is particularly well-known for the ephemeral fog sculptures, which feature in this exhibition as well. These are created by forcing water through tiny nozzles at high pressures, splitting it into a mist of minuscule droplets. This mist hangs in the air, embraces the visitors, and leaves behind a damp trail.

The sculptures blend nature and artifice in subtle ways. They are undoubtedly technical in nature: the fog fills the rooms with a piercing hissing sound, and when it clears it proudly reveals rows of stainless steel nozzles and tubing. But in composition and evolution these mists of water droplets mimic the phenomena we might know from walking through a forest on a chilly morning. In choosing not to work with chemical smoke machines, Nakaya embraces this respect for natural phenomena (although the water she uses is purified). A lot of creative as well as computational work goes into designing these sculptures, including consulting meteorological data from nearby weather stations (which feature in the titles of these sculptures as sequences of numbers), studying the geography of each site, defining technological parameters, and modeling how the fog will look using wind tunnels or 3D software. Anne-Marie Duguet elucidates these artworks in much closer detail for Fujiko Nakaya’s 2012 catalogue of fog sculptures, which we recommend to anyone interested in learning more about them.

The exhibition features two new installments, “Munich Fog (Wave) #10865/I” and “Munich Fog (Fogfall) #10865/II”. The ‘wave’ fog is set up in the central exhibition hall that has been retrofitted to capture water from the fog in a shallow pool. The ‘fall’ flows down the back of the museum building by the Eisbach wave and its surfers. Fog can evoke feelings of mystery or serenity, but can also evoke a powerful sense of unease through its visual resemblances to bellowing plumes of smoke from forest fires, condensation trails from aircraft, mists of pesticide spray over monoculture fields, or miasmatic urban smog. In fact, whilst her sculptures celebrate water and fog as entities in themselves, Nakaya’s work is also saturated with environmental concerns. Throughout our tour of the exhibition, we felt like it spoke conspicuously to some of the central themes of our doctoral program. We’ve chosen three rooms from the exhibition to illustrate this.

Floris Winckel, Livia Cahn

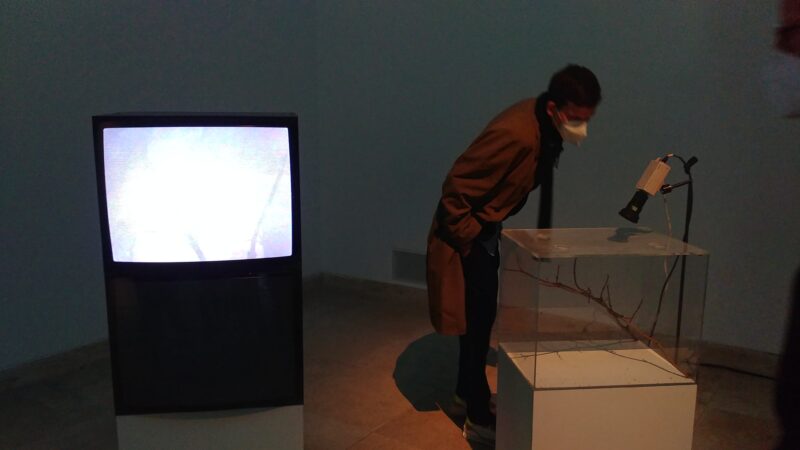

We entered the exhibition from the side entrance, through the outdoor “Fogfall #10865/II”, into a dark room with a tall ceiling, and only three sources of light: A bright white light from one of two CRT-TV screens, a warm orange glow cast over an acrylic box, and a dim orange light illuminating the installation label printed on the opposing wall. A video camera fixed to the side of the acrylic box peers down at a suspended twig. The label describes the installation, entitled “Ride a Wind and Draw a Line (1973/2022)”, as a ‘techno-ecological experiment’ interweaving ‘natural’ and ‘artificial’ categories. Inside the box are walnut orb-weaver spiders, who were likely relocated from just outside the museum. The second TV screen – which was turned off when we were there – would have shown a film made by Nakaya in 1973 (on display in another room) of a spider weaving a web in its natural habitat. There, the spider uses the wind to cast its initial threads. Inside the box, a lack of wind means a lack of web.

The live video feed on the illuminated screen makes this absence evident. Taken together, these two (three) scenes document the parallel realities of the spider at work (or not). Simultaneity is a running theme in Nakaya’s work. Her fog sculptures are constantly in motion, wrapping around and passing through nearby people, simultaneously making them spectators of and participants in the art. But the kind of simultaneity displayed in this installation is one of human and non-human time. The video made by Nakaya in 1973 was recorded using open-reel VCR, which films for a maximum of 30 minutes at a time. In this context Nakaya describes playing a game with the spider, hoping that it would finish by the

time the tape did. Her objective was to show people the ‘spider’s time, not mine’. What she is referring to can be presented as a kind of framing problem: in trying to capture the spider’s experience, she is limited by the frame dictated by the technology she uses. Frames are often thought of as the physical borders which bound an image, but they are in essence a means of concentrating our attention. This attention is bounded both by the film’s physical frame (aspect ratio and resolution) as well as its time-frame. But Nakaya also lets the spider play a role in framing the scene, much like she lets fog dictate its own shape as it moves through space. This way of framing nature and letting ‘nature’ frame itself is a subtle but persistent theme throughout her work. It is also a running theme in our program, whether it be in understanding the aesthetic properties and values of landscapes (Laura Fumagalli), the ways economists frame environments (Danielle Schmitz), the way geologists make sense of the underground (Livia Cahn), or the collaborations between poet and glacier (Anne-Sophie Balzer). We just used the term ‘technology’ to refer to the video camera. But Nakaya also describes the web-making process of the spider as a technology, and in doing so creates a neat contrast. The video camera and TV are quintessential ‘modern technologies’, but here they are placed alongside a ‘natural’ technology of web-weaving. This juxtaposition resonates with what scholars have tried to do over the past few decades, namely, to broaden the scope of what is meant by ‘technology’, and critically analyze our relationships with it (see for example Eric Schatzberg’s “Technology: Critical History of a Concept”, 2018). Our very own Max Pieper is engaged in such work. His project looks at how technologies mediate our perception of reality, specifically with respect to global resource flows. The artwork is ultimately not the image on the screen. It is the confrontation with multiple dualisms: the simultaneous spinning and non-spinning of spider webs; the contrasting representations of spiders in natural and artificial environments; the different notions of natural and artificial technological processes. It is a microcosm of the art-nature-science entanglement that runs throughout Nakaya’s work. Little did we know when we stepped into the next room that this microcosm was going to explode into a staggering art-nature-science multiverse.

~An Environmental Humanities Explosion~

Floris Winckel, Livia Cahn

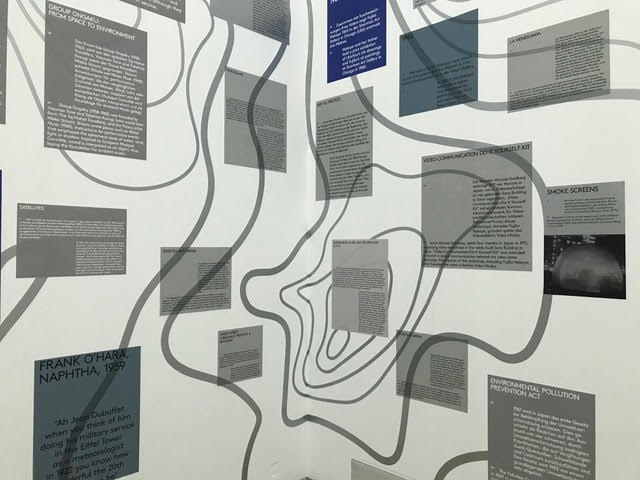

Gone are the bare walls and muted lighting. Having entered the room described as a ‘multiverse of historical events’, we found ourselves surrounded by images, text boxes, and swirly silver lines plastered on the walls. The space has a uniform greenish blue tinge to it, as if underwater, inviting the visitor to swim through the many fragments of events in the modern history of visual technology, experimental art, ecological scholarship, and environmentalism. It is a room dedicated to Nakaya’s formative experiences and prescient environmental concerns. Not unlike the walnut orb-weaver spider, she strings together East Asian and Western artistic and technological ideas into a web of discourses that will be familiar to Environmental Humanities scholars. ~ E.A.T. ~ Atomic clouds ~ protest art ~ video cassettes ~ Greenland glaciers ~ weather forecasting ~ “Parliament of Things” ~ artificial snowflakes ~ earth-monitoring satellites ~ cyberpunk “Dumb Type” ~ geo-engineering ~ The International Day of Mother Earth. A written summary wouldn’t do justice to the experience.

What is noteworthy is how democratically these fragments are displayed. This is not just the work of an artist with an interest in science and technology, nor that of an environmentalist interested in art. Nakaya manages to speak to all these spheres at an equal level. Her productive relationships with scientists, technicians, artists, and environmentalists is a testament to how her work exceeds the sum of its inspirations. If ever there was a model for inter-, cross-, or transdisciplinarity, surely this would be it.

‘You must listen to ice if you want to learn about ice.’

Floris Winckel, Livia Cahn

The final room that we visited is distinct in several ways. Its location on the first floor – separated from the rest of the exhibition by a large staircase – creates a sense of distance. This distance is accentuated by the decor. In contrast to the moody blues and greens on the ground floor, here the light is cream. There are traditional museum display tables, a few paintings, and some old-looking objects. At first glance it seemed like a space disconnected from the journey below, but in fact our final destination had taken us back to the start; the room is dedicated to the artist’s father, whose work greatly inspired hers. Ukichiro Nakaya (1900-1962) became famous for growing the first artificial snowflake in a laboratory environment in the 1930s (needless to say, a significant event for Floris’ project). A physicist by training, he sought to understand how atmospheric conditions affected snow-crystal morphology, producing many important publications and accruing a lively community of researchers around him in his Hokkaido mountain lab. But his work on snowflakes extended beyond the lab. In 1949 he co-founded Nakaya Laboratory, a science film studio which in the following year became Iwanami Productions. In the subsequent 48 years, the studio produced nearly 8,000 educational films, and fostered a new generation of Japanese film-makers; in the post-war period. This room is dedicated as much to this work as to that of its co-founder.

Floris Winckel, Livia Cahn

On display are: numerous photographs of laboratory-made snowflakes, arranged in a back-lit light box for visitors to admire their sheer and delicate diversity; images from Ukichiro Nakaya’s work on spark discharges, plastered on the wall; a display case with a copy of his famous book, “Snow Crystals: Natural and Artificial” (1954), alongside photographs, drawings, and booklets produced by the Museum of Snow and Ice in Kaga City; and original instruments used by Nakaya and his team to create and observe artificial snow crystals. Not on display is the suspended rabbit hair from which the crystals were grown – a little natural-technological detail which would have resonated nicely with the spider’s installation downstairs. Finally, a program of selected films by Iwanami is projected onto a screen at the far end of the room, showcasing rare footage of Nakaya and his team at work in their laboratory. That all these historical documents and objects are exhibited alongside Fujiko Nakaya’s work goes a long way in making explicit the influence these experiments have had on her work, not to mention the fascination with minuscule water bodies. By placing her father’s largely scientific work in the context of an art exhibition, and emphasizing his contribution to educational film-making, Fujiko Nakaya continues to fog up the boundary between the sciences and the arts.

Floris Winckel, Livia Cahn

Leaving the exhibition a few minutes before closing time, we were left with the impression that Fujiko Nakaya’s work does seemingly effortlessly what we’re struggling to do: overcoming disciplines. She fuses different media, aesthetic experiences with activism, concepts of art, nature, and science, in ways that are not at all forced, but rather entirely productive (and – dare we say – natural), such that it becomes difficult to imagine they were ever separate. With these thoughts we quickly stopped by the bookshop opposite the exhibition entrance. And as if to confirm our suspicions that this was actually an Environmental Humanities operation in disguise, there, next to the 2012 catalogue of fog sculptures, we recognized many names: Tsing, Latour, Ingold, Haraway, Ellis, Horn. If these are familiar to you as well, you’ll probably find something in this exhibition that speaks to your interests.

The exhibition is curated by Andrea Lissoni and Sarah Johanna Theurer. It runs until July 31st, 2022. We haven’t even mentioned the wonderful companion website to the exhibition, worth checking out even if you don’t plan to visit in person. For more information, see the Haus der Kunst exhibition page.